Turkey orders detention of 300 people over alleged Gulen links

The Turkish police have launched raids to detain over 300 people suspected of having ties to an outlawed group believed to be responsible for a 2016 coup bid, Turkey's official Anadolu news agency said.

The order to arrest 324 people on Tuesday was made by prosecutors in Turkey's three biggest provinces of Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir and is part of different probes into followers of US-based Muslim preacher Fethullah Gulen.

Turkey accuses Gulen of ordering the abortive bid to topple President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on July 15, 2016.

Gulen denies any involvement in the failed coup.

The Istanbul public prosecutor sought the arrest of 53 active duty soldiers in 15 provinces, including in the metropolis, Anadolu reported.

In the Aegean province of Izmir, the public prosecutor issued 182 arrest warrants with police conducting raids across 42 provinces, including Izmir, DHA reported.

The capital's public prosecutor said it issued 89 arrest warrants in two separate probes, including one looking at the gendarmerie, which is in charge of domestic security.

The Ankara prosecutor's office said 30 suspects had already been detained.

More than 760 people were detained last week in operations across 76 provinces of Turkey's 81 provinces, although 122 suspects were later freed under judicial supervision.

As many as 16 other suspects were released, according to the Ankara public prosecutor's office.

Tens of thousands of people have been arrested over suspected links to Gulen since 2016.

Meanwhile, more than 100,000 people have been sacked or suspended from the public sector.

Despite criticism from Western allies and human rights defenders over the scale of the crackdown, the police operations and probes continue with rigour.

Turkish officials insist that the raids are necessary to remove the "virus" caused by the Gulen movement's infiltration of Turkish state bodies.

The Type 81: Meet China's Very Own AK-47 Rifle

China’s 1980s stopgap rifle may continue to see service far into the twenty-first century.

In the 1980s, China’s small arms were largely inferior to the United States and Russia.

The PLA was mostly armed with the Type 56 assault rifle, a clone of the original AK-47, and the Type 56 carbine, a clone of the Soviet SKS. There was an abortive attempt to combine the characteristics of these rifles in the 1960s which culminated in the Type 63, an SKS-looking select-fire rifle that used elements of the AK operating mechanism such as a rotating bolt and fed from AK magazines. The Type 63 was too heavy and lacked a pistol grip and inline stock to afford controllability in fully automatic fire. It was an outdated rifle when it was introduced, especially compared to the American M16 and Soviet AKM.

The PLA realized this and began development of a new 5.8mm caliber the rifles for it, which eventually became the QBZ-95. However a “stopgap” rifle was needed, to quickly replace the Type 56 AKs. From this requirement, the Type 81 was born.

(This first appeared several years ago.)

The Type 81 was not meant to be just a rifle. It was meant to be a test of the Chinese ability to develop small arms on its own, instead of simply adapting other designs. Unlike the Type 63 carbine before it, the Type 81 used a gas system of purely Chinese design. It also addressed flaws of the earlier rifles in light of combat experience in the Sino-Vietnamese war. In an attempt to make the rifles more modular and adaptable, the integral folding bayonet of the Type 56s and Type 63 was scrapped in favor of a removable knife bayonet and the provision to mount an underslung grenade launcher. The barrel was also lengthened and given a spigot to allow the Type 81 to launch rifle grenades. It also featured a novel sighting system, ditching the AK and SKS rear leaf sights in favor of a shielded aperture that resembled the early M16s.

The earlier Type 56 assault rifle was also considered to have too poor accuracy in single fire mode (oddly, contrary to the Soviet experience in the 1950s). This flaw was also in the minds of Chinese designers, who specifically designed the Type 81 to be more accurate than the Type 56, utilizing a short-stroke gas piston system as opposed to the long-stroke used in the Type 56. The barrel manufacturing techniques were also improved, and the barrel itself is longer relative to the Type 56 assault rifle.

The end result was an impressive fusion of designs. The Type 81 was reliable, able to shoot around 15,000 rounds on average without parts breaking or needing replacement. It was more accurate than a standard AK in 7.62x39, with less recoil. The provision for soldiers to launch grenades two different ways was added. Apart from some early issues such as the sight zero being thrown off by launching rifle grenades, the Type 81 was loved by the soldiers who were issued it. It saw its first action in the Sino-Vietnamese border conflicts.

Despite its success, in the end, the Type 81 was still a stopgap rifle. What the PLA really wanted was a rifle in a new true intermediate caliber: 5.8mm. As this caliber started to reach maturity, some versions of the Type 81 were chambered in it as testbeds for the new caliber. It was eventually replaced in frontline PLA service by the QBZ-95. That wasn’t the end of the road for the Type 81 though. It continues to see service in the People’s Armed Police, upgraded with Picatinny rails that allow it to mount modern optics, and has proven to be an adaptable design. When a new series of Chinese DMRs were revealed around 2015, they too were derivatives of the Type 81 design, despite the new name of CS/LR-14. These new DMRs are the Chinese answer to compete with other 7.62 DMR rifles such as the FN SCAR and SR-25 on the global export market. China’s 1980s stopgap rifle may continue to see service far into the twenty-first century.

Charlie Gao studied political and computer science at Grinnell College and is a frequent commentator on defense and national-security issues.

Image: Creative Commons.

Yun Ch’iho Meets Jim Crow

What did a Korean Protestant make of Dixie in the late nineteenth century? Consider the case of Yun Ch’iho.

Yun Ch’iho — courtesy of Emory University

Yun Ch’iho — courtesy of Emory University

Yun was a member of the Korean aristocracy, a scion of the prestigious and powerful Haep’yong clan. He enjoyed all the privileges of the royal Court, which included wealth and education.

Until he didn’t. After being wrongly implicated in an abortive Korean reform coup, Yun fled to Japan in 1884. Then he went to China, where he was converted to Christianity by a Methodist Episcopal missionary. Seen as a young man with much potential, Yun was sent by church leaders to Vanderbilt and Emory to study theology.

America, Yun was told, was a promised land. But he quickly realized that was not true for nonwhites. Hotels in Kansas City refused to give him lodging, and so he had to sleep overnight in the railroad station. As William Yoo, author of the terrific book American Missionaries, Korean Protestants, and the Changing Shape of World Christianity, 1884-1965, puts it, “As he better understood the social scripts embedded in American culture, Yun received an education in racial inequality, white privilege, and sexual boundaries.”

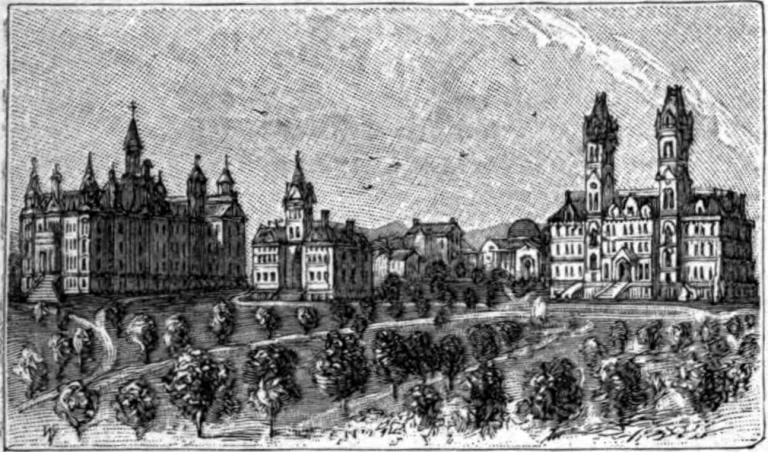

Vanderbilt University — courtesy of Appletons’ Cyclopedia of American Biography (1889)

Vanderbilt University — courtesy of Appletons’ Cyclopedia of American Biography (1889)

Yun may have been a quick study in religious studies. He got high A’s in theology and homiletics in his first year at Vanderbilt, his professor remarking that Yun “possessed the keenest mind of any student who sat in his classes of over forty years of teaching.” But he could not solve the problem of race. As the years passed, the list of Yun’s grievances grew:

He connected his experiences with others laid low by the “civilized” West. He spoke of Britain’s opium trade with China and the unjust treatment of indigenous peoples in North America. He was revolted by the influence of social Darwinism. Expecting missionaries to be “human ambassadors of divine grace and universal justice,” he discovered that some detested their potential converts because of their race. After hearing one missionary’s racist sermon, he refused to partake in the Lord’s Supper with him. “What he said about the people here not even thinking of Chinamen and Japs as their equals kept me from the Lord’s table. For if the people are too proud to regard us as equals, then I am too proud to claim that equality by taking the Supper with them.”

Complicating this narrative is Yun’s own troubling racial views. He criticized this same missionary for classifying Asians on the same level as African Americans. This, he said, was “very unfair and unjust.” Indeed, Yun’s diary, which critiques Southern whites for mistreating blacks, itself exhibits a deep racism. As he visited black churches, he was turned off by preaching that he said contained “no text, no logic, no rhetoric, no grammar.” He described the sermon as “a string of inarticulate sound and articulate nonsense seasoned with Scripture quotations or allusions,” and he dismissed the dancing, fainting, embracing, shrieking, and kissing he observed in African American worship.

It can be tempting to tell single stories of non-American Christians as either benighted savages or naïve innocents—and of American internationalists as either cold imperialists or compassionate saviors. But globetrotting Christians, when understood in the fullness of their contexts and complexities, consistently defy such tropes. Yun Ch’iho, as depicted by Yoo in this skillful and empathetic history, embodies these realities.

No comments:

Post a Comment